This year marks the 35th anniversary of the groundbreaking documentary Paris is Burning. The film, released in 1990s, presented a slice-of-life view into the ballroom scene in New York City in the 1980s, which was led predominantly by LGBTQ Black Americans and Latinos. The extravagant “balls” of that period served multiple functions, providing family, a sense of community, and an outlet for creative expression for individuals marginalized by mainstream society due to their sexuality, race, and class.

Further, the balls were a means of resistance to the status quo, allowing those who participated to feel like deserving, full-fledged human beings in a world that constantly told them they were the cast-off “other.” While we still celebrate the cultural significance of the film, it’s important to note that many of the problems it touched upon still plague society today, as the fight against homophobia and the persecution of the LGBTQ community continues to be a prevalent issue.

Directed by Jennie Livingston, Paris is Burning was filmed in the second half of the eighties and chronicles what is known as the ball culture of New York and the African American, Latino, gay, and transgender communities who spearheaded it. The documentary both highlights the impressive talent and creativity of the ballroom scene while providing intimate portraits and perspectives of the individuals who embodied it.

Raw interviews and candid interactions give a sense of both strength and struggle, all while educating those unfamiliar with the history of ball culture a glimpse into a world which would later heavily influence mainstream popular culture. The year in which the film debuted is significant in itself, for it was the time when HIV/AIDS was killing thousands, and ballroom culture was not left unscathed.

HIV-related mortality rates rose steadily in the 1980s. At this time, the virus and the disease it triggered was closely associated with gay men and therefore deemed the “gay plague” by corporate media. During President Ronald Reagan’s time in office, he refused to speak publicly about HIV/AIDS for several years. It wasn’t until 1987, at an AIDS conference in Washington, that he addressed the issue. By then, 36,058 Americans had been diagnosed with the disease, and 20,849 had already died. When Vice President George H.W. Bush succeeded Reagan in the White House, Bush continued to claim that AIDS was a “behavioral” disease.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in 1989, the first year of the Bush administration, there were 21,628 AIDS-related deaths in the United States. This number would rise to 24,524 in 1990, 28,569 in 1991, and 32,407 in 1992. The looming threat of the disease does not go unaddressed in Paris is Burning, and it would impact the lives of many who starred in the doc years after the it premiered.

Despite the danger of disease encroaching on their community, the stars of the film continued to shine bright, focusing on their drive for success, acceptance, and overall happiness. Numerous queens, “mothers,” and “children” of the ballroom scene are showcased, forever imprinting their compelling stories and perspectives on viewers as we’re invited into their world.

There’s a lot of history packed into the film. Various figures explain terminology and its origins to the unfamiliar, and anyone watching today would be well aware of just how much Black gay drag culture is intertwined into mainstream vernacular, behavior, and communication.

It’s explained that ballroom shows have a number of categories that grew even more inclusive over the years to allow people a chance to compete beyond flashy sequin dresses and sky-high costume pieces that were more prevalent in the 1960s. Many of the categories, such as Executive Realness, Military, High Fashion Evening Wear, and Luscious Body, went beyond contestants putting on relevant clothes and walking the runway.

Oftentimes, the ballrooms provided those who participated a means of acting out roles that they were often excluded from in real life. At a ball, one could be the CEO of a multi-million-dollar company, if they wanted, or a high-fashion supermodel. Discrimination—by class, education, race, and sexuality—meant such avenues were closed in the real world. The balls were a chance to express that “realness,” to pass, and to—if only for a night—embody the roles they weren’t allowed to play in mainstream society, with a dash of ballroom flair.

“Houses” are explained as functioning like alternative families, providing shelter for those ostracized by conventional support systems. These houses were a formation of ballroom attendees and performers, all striving for prestige and accolades in the ball scene. They are half-jokingly described by one interviewee as “gay street gangs” whose battles play out on the ballroom floor.

In retrospect, it’s obvious just how much mainstream pop culture adopted and adapted from the balls. The singer Madonna may have made voguing mainstream with her hit song, but she was inspired by ballroom culture. The same goes for now often-used terms on social media like “throwing shade” (meaning to insult someone without directly insulting them) and “reading” (meaning to reveal someone’s flaws, often in a humorous or pointed way). These are just a few of the terms explained in the film.

It all demonstrates the expansive history how the ball scene and drag culture—not only in the ’80s but for decades before—is so intertwined with and a part of American culture. For the balls didn’t just start during the Reagan era, not even the 1950s and ’60s. They go back even further, to the early 1800s with a former enslaved Black gay man named William Dorsey Swann.

In the late 1880s, Swann began hosting private balls known as “drags,” thought to be derived from the term “grand rag,” meaning masquerade balls. Swann is now credited with initiating the first documented “drag balls” in American history. Journalist and historian Channing Gerard Joseph wrote of how the get-togethers provided a safe space for gender expression, as guests wore women’s clothing or men’s suits while sometimes competing in a “resistance dance.”

Swann was also considered the first known person to self-identify as a “queen of drag.” Even the notion of being a “queen” is connected to Black liberation, as Swann was inspired by the “Queens of Freedom” crowned at Emancipation Day parades in Washington, D.C., during the late 1800s. At those events, Black women were crowned as representatives of their neighborhoods to celebrate the city’s emancipation from slavery.

Swann would hold these parties despite an increasing number of laws banning cross-dressing. Arrested numerous times, the trailblazer was defiant and fought for his innocence and rights, coming to be seen by many historians as an early queer activist. And while Swann’s name is not mentioned in Paris is Burning, that influence and connection are deeply felt in the film.

This is a part of history that goes unrecognized not just by mainstream heteronormative society, but also by the white gay male culture that often predominates within the broader LGBTQ community. So much of the pioneering work and cultural creation of Black, Latino, poor, and femme members of the queer world gets coopted but goes uncredited.

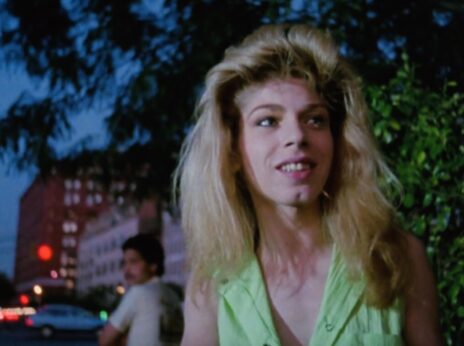

Ballroom legends and emerging talents at the time—like Pepper Labeija, Kim Pendavis, Freddie Pendavis, Dorian Corey, Venus Xtravaganza, Angie Xtravaganza, Willy Ninja, and Octavia Saint Laurent—give us a view into their lives as gay individuals trying to exist and thrive. The struggles of class and race are candidly touched upon, offering sobering statements and at times enlightening nuggets of truth. Not everything in the film can be deemed politically correct or progressive, but above all else, there is honesty from those speaking their truth.

The tragedy of the unsolved murder of Venus, addressed later in the film, gives an all too real jolt of reality, showing the struggles many of these figures faced attempting to survive on the streets of New York City. Particularly, through the case of Venus, viewers get a glimpse of the danger transgender women of color face. They are victims of violence at higher rates than other populations, a reality that many in society have only woken up to recently.

Paris is Burning is a public service announcement of the danger and alienation faced by the communities who rely on ball culture for support. One of the lessons to take away from the film in 2025 is that while gains have been made, there is pushback against the moves toward greater equality, and the far-right is again intensifying its targeting of the LGBTQ community.

According to GLAAD (Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation), the current White House administration, headed by President Donald Trump, has initiated at least 255 attacks against LGBTQ people in “policy and rhetoric.” One of those included the president’s executive order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” which withdrew federal recognition for transgender people.

The Supreme Court also recently cleared the way for the Trump administration to enforce a Department of Defense policy banning transgender people from serving in the military. The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) is currently tracking 588 anti-LGBTQ bills filed across the United States.

Suffice to say, the sentiments expressed by those in Paris is Burning regarding the persecution of the LGBTQ community were well-founded and unfortunately still describe the political situation today.

While we can celebrate Paris is Burning, the best way to honor its legacy is to keep the spotlight on the fightback against these attacks. Another way is to acknowledge the cultural impact of the ball scene on a society where there are those who wish to whitewash history in a way to erase this influence. The ballroom scene may seem niche to the uninitiated, but Paris is Burning makes it clear that it’s ingrained in the fabric of this country’s culture—past and present.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!